by Cindy Lin

4S 40th Annual Meeting was held from 11-14 November 2015 at Denver, Colorado. I will highlight some of the crucial moments during the conference that relate to both my research interests as well as other insightful moments in this short reflection of particular panels and informal conversations I have participated in.

In this conference, I presented “(Un)making Indonesia: Local Particularities of Grassroots Technological Production in Hackerspace” as part of the (incidental) chairing of a panel called “Hackerspaces and Makerspaces” on 11/14, Saturday. I used Anna L. Tsing’s metaphor of friction[1] to discuss the disruptions and opportunities experienced by Lifepatch, a citizen laboratory and hackerspace invested in the intersections of art, science and technology to produce do-it-yourself (DIY) tools and platforms which critically respond to local political and socioenvironmental problems. The metaphor, friction, allows me to elucidate the vulnerable yet flourishing encounters they have productively engaged with in transnational projects and collaborations.

While many panellists acknowledge the plural meaning of making today, there are discussions which surround the kinds of expertise that can and should enter these circles to write about personal fabrication. Some of the more memorable discussions by Science and Technology Studies (STS) scholars, designers and engineers presenting at 4S are questions surrounding who has the right to write about maker culture, what counts as being a maker and how is making articulated in different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Other discussions went so far as to argue that STS scholars might have to learn how to ‘make’ in order to write about maker culture. I vehemently believe that being able to prototype with 3D printers does not make one any better of a researcher about maker culture if he or she is unable to articulate their stance clearly and with nuance.

The second day (11/12) of the 4S conference started out with an invigorating panel session on ‘Translational STS: From Seeing to Doing/Making/Changing’. I was most intrigued by James W. Malatiza’s[2] presentation “Bodymancy: STS as a Link between Bodyhackers and the Medical Community” and his explication of the relationship between individuals who are biomodification practitioners and their relationships with medical practitioners and professionals. Malatiza attempts to bring the concept of “hyperobjects” by Timothy Morton[3] in the conversation of a modified body, showing how sensitivity to the various invisible viscosity and stickiness of micro-elements such as radio waves are made more apparent to the modified body.

Since biohacking is one of my main research and practice interest, “Joining Reference and Representation – Citizen Science as Resistance Practice” on 11/13 also excited me with the panel’s focus on the politics of digital mapping, actionable science, and the meeting of various domain expertise. I was most taken by Max Liboiron’s[4] “Charismatic Data in Citizen Science Environmental Monitoring” where Liboiron discusses the potency of visualisation when tackling representation of scientific data. From campaign images by large non-governmental environmental organization such as Greenpeace to the milder forms of microscopic scientific visualisation, Liboiron warns against particular kinds of charismatic data which “can get you in to trouble”. In other words, scientific representations can be sometimes, misconstruing and edgy.

In the last panel that I have attended “Resistant Matter: Histories, Politics and Science of Multispecies Entanglements,” one of the panellist, Andrea Nunez Casal[5] in “Impacted Immunities: Anthropocene Bodies and Environments in Microbiome Research” discusses how the framework of bio-inequalities is crucial for explaining how themes such as geopolitics, southern cultures and antibiotics is still present in the politics of colonial science practised in the global south. Where state borders and scientific regulations are relaxed in southern cities, capitalism encroaches on the vulnerability of biosoverignity in these sites as they clamour for more “un-impacted” and “isolated” genetic samples for the production of antibiotics. It might be useful here to recall how biosovereignty was conceived in discourse during the H5N1 Influenza outbreak (2005-2013) when World Health Organisation (WHO) shared viral samples from Indonesia to in turn, encourage the fabrication of patented and unaffordable vaccines back to infected Indonesians.

But what resonated throughout the immense bleakness of some of the unresolved, Janus-faced complications of science and technology discussed, scrutinised, and dissected during 4S is the trope of “hope” in society. Perhaps it was the optimism driven by Denver’s frothy beer or the snow-capped hills that bring forth new ways of understanding my own embeddedness in other kinds of ecologies, but I was inclined to think about micro-acts of resistance and desires for new alliances and opportunities. Steven J. Jackson[6] also discussed the trope, “hope” as resonant throughout the panellists’ presentations in “Contested Spaces of Innovation: Reimagining Postcolonial Geographies”. I am, too, fully taken by this proposition and hope to redeem Hope as a way to think about personal fabrication in periphery sites.

I see in my field sites – Detroit, Yogyakarta, Surabaya, Jakarta, Bandung – an immense sense of Hope in hackerspaces and makerspaces. While one may easily associate the “Hope” project with blind optimism, naïveté, and the uncritical, I see it as a project that exceeds beyond such loaded and terribly misunderstood words. Look beyond the criticisms towards urban city planning, educational policies and neoliberalism, there isn’t a murky vision of loathsome excitement but a hope which scares those who remain hopelessly cynical. Hope does not smear away differences. Instead, Hope revels in the tiny instances of possible shifts towards aggregates of productive misinterpretations and awkwardness so that we can better understand how we might like to move forward. However gingerly.

I will quote here a sentence from Cultural Anthropology’s “Reclaiming Hope” by Eben Kirksey and Tate LeFevre,

While hopes can indeed have toxic properties, optimistic dreams also have the indeterminate qualities of the pharmakon—a substance capable of acting as both poison and remedy depending on the dose, the circumstances, and the context (Stengers 2010, 29).[7]

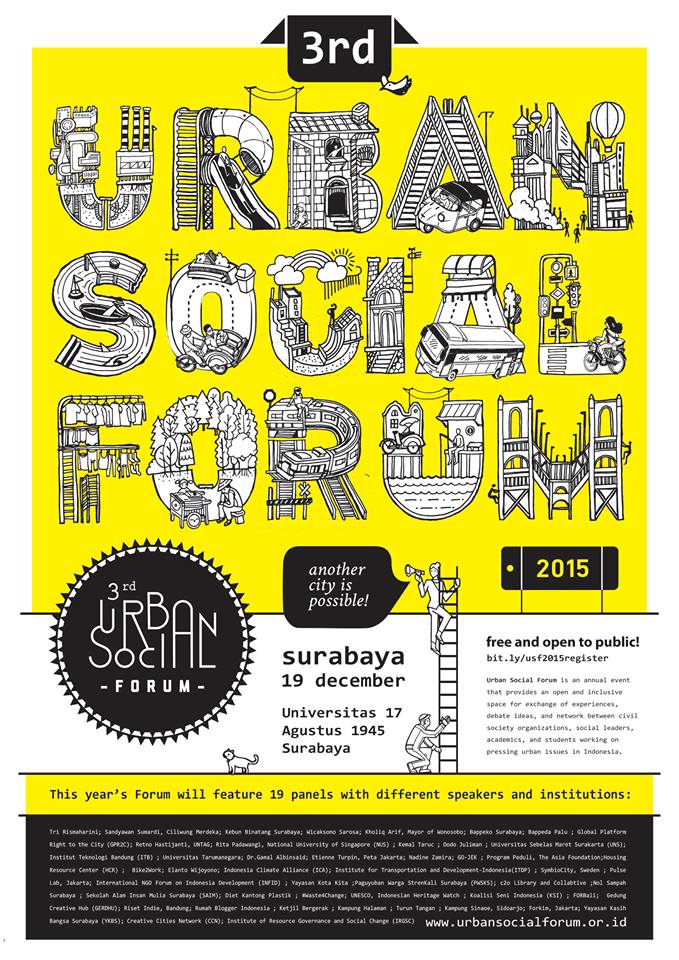

I will be at the 3rd Urban Social Forum organised this December 19, 2016 in Surabaya, Indonesia where I will watch, listen and learn from my interlocutors and other grassroots collectives, non-governmental organisations and start-ups from Indonesia and other parts of the world. Perhaps we will relish in pharmakon one more time.

Written by Cindy Lin

Links

4S: http://4sonline.org/

3rd Urban Social Forum: http://urbansocialforum.or.id/

[1] Lecturer in Science and Technology Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

[2] Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton University Press, 2005.

[3] Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. 2013.

[4] Assistant Professor in Sociology and Environmental Sciences at Memorial University of Newfoundland

[5] MPhil/PhD candidate at Goldsmiths, University of London

[6] Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of Information Science at Cornell University

[7] See authors’ introduction in “Reclaiming Hope” issued online in the journal, Cultural Anthropology http://www.culanth.org/curated_collections/20-reclaiming-hope